December 7, 2017: Nigeria has unveiled a major railway expansion project to ease congestion on roads and to boost the economy, writes Ijeoma Ndukwe from the commercial capital, Lagos.

A train pulls into Ebute Meta station on mainland Lagos. The station is housed within an old railway compound built during British rule in Africa’s most populous state with a population of more than 185 million.

Some 57 years after independence, colonial buildings, relics of a bygone era, remain the headquarters of the Nigerian Railway Corporation (NRC).

Driving towards the station, I catch glimpses of decades-old tracks overgrown with grass.

Discarded carriages, train parts and equipment are scattered around the compound.

A 30-minute train ride upstate takes us to a station called Iju, in a suburb of Lagos.

We are at a building site alongside the old railway line where workers are laying the foundation for new train tracks by hand.

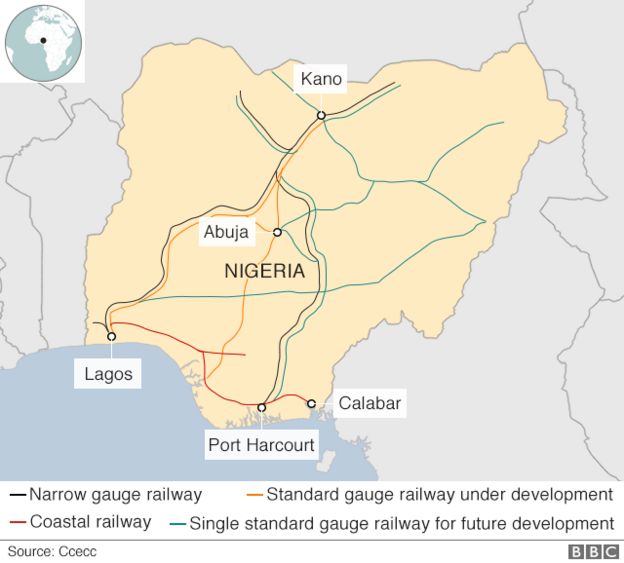

They are constructing 144km (90 miles) of modern tracks connecting the bustling coastal city of Lagos to Nigeria’s third-largest city, Ibadan, in the second stage of the government’s railway modernisation project.

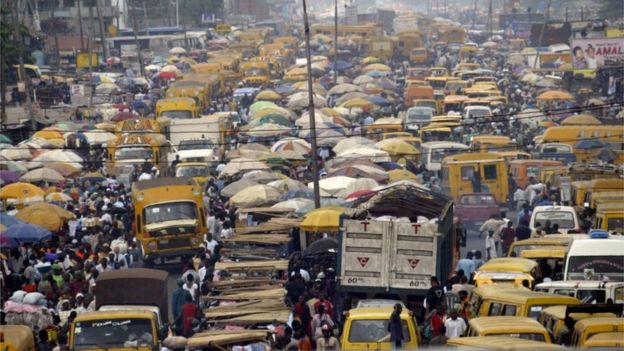

Lagos is notorious for its traffic jams

Lagos is notorious for its traffic jamsThe first – the railway between the capital, Abuja, and the northern city of Kaduna – was completed last year.

The third will be to link Kano in the north of the country to the coastal cities of Port Harcourt and Lagos in the south.

Damaged roads

The work, NRC managing director Freeborn Okhiria explains, is aimed at upgrading the rail to a wider track.

“It’s easier and faster and cheaper,” he says. “You can move more people, more goods, more speed, better poundage of the rail – instead of moving 40 tonnes per wagon you can move 80 tonnes.”

For Nigerians who are forced to deal with congested, damaged roads after years of neglect in densely populated cities such as Lagos, the lines cannot come soon enough.

“It’s going to ease a lot of things, it’s going to bring development, it’s going to make life easier for the common Nigerian,” Gabriel Shepkong, a naval officer, tells the BBC.

But it will come at a price: the final bill is estimated at $36bn (£25.9bn).

Yet Rotimi Amaechi, the minister of transport, says it will be money well spent as it is “critical to development” in Nigeria.

“The cost of goods, including commodities and services, are on the rise because of [the] poor transportation network,” he tells the BBC.

“Most countries which have no railway are slow to develop. We think that it’s time to increase the pace of development.”

Cheap Chinese loans

But this is not the first time Nigerians have heard about government plans to construct new railways and fix antiquated tracks – there has been talk of this for decades.

Mr Okhiria explains that past ambitions to upgrade the railways had been thwarted by inadequate funding.

He says the Lagos to Ibadan line – a $1.5bn (£1.1bn) scheme – has been fully funded.

He is confident that the NRC will meet the deadline for completion this month. Although most of the money came from the Export-Import Bank of China, the government played its part as well, Mr Okhiria says.

As for funding the rest of the project, Mr Amaechi is hoping that China will step in once more.

Its concessionary loans are at interest rates of 1.5% – a price the minister describes as “very cheap” compared to commercial loans with interest of around 5%. In return for cheap loans, Chinese contractors are being used for the construction process.

A new deal, signed with a group of infrastructure companies led by General Electric, should create at least 100,000 jobs, the minister says.

Although the West African state is opening up its rail system to private investors, many Nigerians remain unconvinced that the entire project will see fruition because of the government’s past failures.

“Personally, I don’t have faith they would deliver on it,” says Dumebi Akbagkoba, a Lagos businessman.

“More than half [of the money] would be squandered and the rest would be used to do a shoddy job, which may lead to disasters.”

Experts are not surprised by the public scepticism.

“We have had several initiatives with previous governments talking about infrastructure, planning around infrastructure and we’re yet to see tangible results,” Yetunde Odedokun, an infrastructure analyst at First Bank of Nigeria, tells the BBC.

“When the same conversations come up and we see the same course of action such as borrowing, it does raise concern.”

But Mr Amaechi dismissed the concern, saying that the Abuja to Kaduna line has already generated $1m (£740,400) in revenue.

“The best thing to do is to borrow and fix it. Will future generations be happy that we don’t construct the railway or infrastructure?” he comments.

Ms Odedokun fears that the project will slow down ahead of the 2019 general election – something that tends to happen in Nigeria with long-term projects as ruling parties divert money towards building easier projects, like clinics, to win votes.

She, therefore, urges Nigerians to make sure that the government pushes ahead with expanding the network, so that it improves their quality of life and that of future generations.